Food labels review for entry to the US, EU and UK markets.

Temporary COVID-19 Policy for Receiving Facilities in Meeting FSMA Supplier Verification Onsite Audit Requirements

Wednesday, 14 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

As the global pandemic of COVID-19 continues to bring about turmoil and health threats, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued guidance to communicate the temporarily drop of the supplier verification onsite audit requirements for receiving facilities and importers under the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) provided other supplier verification methods are used instead. The Preventive Controls for Human Food (PC Human Food) rule requires receiving facilities to conduct supplier verification activities based on the hazard analysis conducted as part of their written Food Safety Plan. These verification activities generally include onsite audits, sampling and testing, or a review of food safety records. Receiving facilities may determine onsite audits to be the most appropriate supplier verification activity. However, many governments have taken strict measures to limit unnecessary inland and out-land travels in an effort to curb the spread of the COVID-19 coronavirus. Such much needed restrictions may impact the ability of receiving facilities to conduct or obtain onsite audits of their suppliers. Therefore, the guidance outlines the circumstances under which FDA does not intend to enforce the requirement to conduct or obtain an onsite audit of a food supplier when the food supplier is in a country or region covered by a government travel restriction or advisory related to COVID-19. The FDA anticipates that receiving facilities will resume onsite audits within a reasonable period of time after it becomes practicable to do so, and update their food safety plans accordingly. FDA intends to provide timely notice before withdrawing this policy. Specifically, FDA does not intend to enforce the requirement foran onsite audit in the following circumstances: A receiving facility has determined that an onsite audit is the appropriate verification activity for an approved supplier, as reflected by its written food safety plan or FSVP; The supplier that is due for an onsite audit is in a region or country covered by a government travel restriction or travel advisory related to COVID-19; Because of the travel restriction or travel advisory, it is temporarily impracticable for the receiving facility to conduct or obtain the onsite audit of the supplier; and The receiving facility temporarily selects an alternative verification activity or activities, such as sampling and testing food or reviewing relevant food safety records, and modifies its food safety plan to incorporate the alternative activity or activities. The alternative verification activity or activities are designed to provide temporary assurance that the hazard requiring a supply-chain-applied control has been significantly minimized or prevented during the period of onsite audit delay. FDA anticipates that receiving facilities will resume onsite audits within a reasonable period of time after it becomes practicable to do so, and update their food safety plans accordingly. FDA intends to provide timely notice before withdrawing this policy. Sources: The Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Constituent Update

- Published in Covid-19

Microbiological quality of ready-to-eat fresh vegetables and their link to food safety environment and handling practices in restaurants in Lebanon

Thursday, 08 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

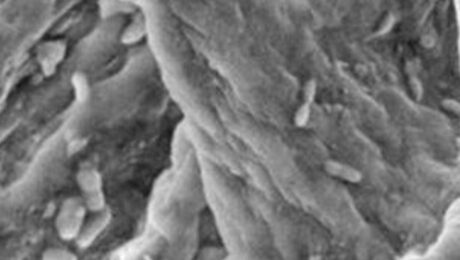

The increased consumption of ready-to-eat (RTE) salads outside homes as a result of a fast paced lifestyle, awareness on their nutritional attributes and enhanced processing technology is well documented. Outbreak investigations often indicate that food service establishments greatly contribute to food-borne illnesses involving fresh produce. Fifty small and medium sized (SME) restaurants in Beirut were surveyed for their food safety climates. A total of 118 samples fresh-cut RTE salads vegetables and 49 swabs of knives and cutting boards were collected for microbiological analysis. A number of food safety practices concerns were identified in this study. The general lack of cleaning and sanitization procedures combined with a clear evidence of cross-contamination opportunities were generally reflected in the overall unsatisfactory quality of RTE vegetables. The majority of SMEs were unaware of the significance of applying control measures when handling vegetables and of the fundamental requirements for separate sinks used for hand-washing and washing vegetables. The inappropriate sanitation measures were not applied in 60% of the premises and a large percentage of food businesses (64%) lacked hand-washing sinks. A large proportion (84%) reported that the wash water was neither treated nor filtered and did not use sanitizers. More than half of the RTE salad vegetables were unsatisfactory due to E. coli and Listeria spp. counts that exceeded the criteria limits >100 CFU/g indicating poor hygienic practices and sanitary conditions. High frequency of S. aureus was also observed indicating poor hygiene practices of food handlers. Presence of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. were traced back to samples obtained from restaurant that had no hand-washing sinks, fresh vegetables washing sinks, and adequate preparation and storage areas; the corresponding inspection rating recorded 32 over 100 possible points. The high microbial population size on chopping board surfaces offered an additional assumption for the actual contamination levels observed on RTE vegetables. As the correlation between the total inspection scores and the microbiological indicators were found not significant, our study confirmed that the total inspection scores per se would not directly indicate the microbiological safety of RTE vegetables in the restaurants and that the strategy of end-product testings do not and will not provide safe vegetables to consumers. Interestingly, there were variations in microbial counts and a significant correlation of high Listeria levels with individual inspection components, i.e., the inadequate cleaning and poor cross-contamination preventive measures, which emphasized that shortfalls in those particular points in the processing environment possibly indicate the presence of pathogens, e.g., L. monocytogenes on fresh vegetables. Therefore, the applications of critical control points for the preparation of fresh salad vegetables and personnel training on the associated bacterial hazards are fundamentals, particularly when salads are prepared in small working facilities in SMEs. The high microbial loads in RTE vegetables found in this work serve as an indicator for the need to promote awareness and a guidance for local authorities on the critical areas commonly identified in the SMEs that most likely affect the safety of fresh vegetables. It underscored the vigilant cleaning and sanitation procedures to reduce or eliminate contamination and cross-contamination risks that may occur at the pre-farm gate and throughout the supply chain stages.

- Published in Ready to eat vegetables

The transfer rate of Salmonella Typhimurium from one contaminated parsley to other consecutively chopped batches- Modeling “Tabbouleh” preparation

Thursday, 08 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

It is becoming more evident that Salmonella-associated outbreaks are not limited to contaminated foods of animal origin; they are periodically linked to consumption of fresh produce, including parsley and lettuce and S. Enteritidis and S. Typhimurium have been commonly isolated from fresh vegetables. Salmonella spp. can be transferred to the food chain directly from human or animal faecal sources, run-off of nearby farms, untreated manure, or from contaminated irrigation water. Additionally, there are various routes for cross-contamination in the kitchen and processing environments. Of food contact surfaces, cutting boards were shown to represent critical risk factors of cross-contamination and recontamination events. In many Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries, leafy green parsley is typically eaten raw and prepared by fine chopping several batches. Because of the convoluted nature of parsley leaves and no precedent for transfer studies with this vegetable, we chose parsley to evaluate the transfer rate of S. Typhimurium in scenarios that resemble normally occurring operations in restaurants and home kitchens. The aim was to quantify the transfer rate of Salmonella across all chopped batches from one originally contaminated bundle of parsley. The transfer of bacterial cells to parsley chopped via water washed cutting board recorded high values, 64.0%. S. Typhimurium was apparently readily transferred into cutting boards, and later was capable of contaminating chopped parsley both at instant contact and at 24 h after washing the cutting board with water or soapy water combined with sponge scrubbing, with the ability to cross-contaminate the entire batches of leafy greens. Interestingly, considerable amounts of bacteria were transferred to 6 sets of clean parsley even when the contamination levels of parsley at the source was low. It was evident in this study that the density of bacteria can remain constant up to 24 h supported by nutrients abundance. We believe that the survival of S. Typhimurium for a prolonged time (24 h) has been probably sustained by remaining substrates from parsley juice within knives-scars and fissures on the plastic boards’ surfaces which have been shown to be very difficult to clean and disinfect, although this may vary among the types of plastic cutting boards.Apparently, the simple domestic washing methods applied in restaurants using water and soapy water with sponge scrubbing (Faour-Klingbeil et al., 2016 http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0023643816304625) reduced the transfer rate to all batches of parsley chopped subsequent to the contaminated samples on the same surface, but it did not effectively eliminate the risk of cross-contamination at instant and 24 h exposure to bacteria. Therefore, the application of additional sanitation procedures such as hypochlorite solution should be a fundamental requirement after use with fresh produce not only after use with raw meat and poultry, especially as parsley is not further treated (ready-to-eat) and if there is a likelihood of inadequate food safety measures at harvest and post-harvest stages.

- Published in Ready to eat vegetables

The Microbiological Safety of Fresh Produce in Lebanon-A holistic “farm -to-fork chain” assessment approach

Thursday, 08 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

The consumption of unsafe fresh vegetables has been linked to an increasing number of outbreaks of human infections. In Lebanon, although raw vegetables are major constituents of the national cuisine, studies on the safety of fresh produce are scant. This research employed a holistic approach to identify the different stages of the food chain that contribute to the microbiological risks on fresh produce and the spreading of hazards. A thorough analysis of the institutional and regulatory framework and the socio-political environment showed that the safety of local fresh produce in Lebanon is at risk due to largely unregulated practices and shortfalls in supporting the agricultural environment as influenced by the lack of a political commitment. Microbiological analysis showed that the faecal indicator levels ranged from <0.7 to 7 log CFU/g (Escherichia coli), 1.69-8.16 log CFU/g (total coliforms) and followed a significantly increasing trend from fields to the post-harvest washing area. At washing areas, Salmonella was detected on lettuce (6.7% of raw vegetables from post-harvest washing areas). This suggested that post-harvest cross-contamination occurs predominantly in the washing stage. At retails, a combination of observation and self-reported data provided an effective tool in assessing knowledge, attitudes, and practices. It showed that the food safety knowledge and sanitation practices of food handlers were inadequate, even among the better trained in corporate-managed SMEs. Overall, the microbiological quality of fresh-cut salad vegetables in SMEs was unsatisfactory. The link between Staphylococcus aureus and microorganism levels on fresh salads vegetables and the overall inspection scores could not be established. On the other hand, inspection ratings on individual components, e.g., cleanliness and cross-contamination preventive measures showed significant correlation with Listeria spp. levels. Together, results confirmed that inspection ratings don’t necessary reflect the microbiological safety of fresh vegetables and that the application of control points of risk factors that likely to contribute to microbial contamination in the production environment are essential. The washing methods were limited in their effectiveness to reduce the contamination of parsley with Salmonella. In general, the pre-wash chopping and storing of parsley at 30ºC reduced the decontamination effect of all solutions, including sodium dichloroisocyanurate which was reduced by 1.3 log CFU/g on both intact and chopped leaves stored at 30ºC. In such conditions, the transfer rate of Salmonella from one contaminated parsley to subsequently chopped clean batches on the same cutting board(CB) recorded 60%-64%. Furthermore, the transmission of Salmonella persisted via washed CBs stored at 30°C for 24 h. It is recommended to keep parsley leaves unchopped and stored at 5ºC until wash for an optimum decontamination effect and to apply vigilant sanitation of CBs after use with fresh produce. This research presented important data for quantitative risk assessment for Salmonella in parsley and useful descriptive information to inform decision-makers and educators on microbial hazards associated with fresh produce in Lebanon. It also highlighted the risks areas that require urgent interventions to improve food safety. Considering the complex institutional and political challenges in Lebanon, there is an obvious need to direct development programs and support towards local agriculture production, effective education strategies and growing awareness of consumers and stakeholders on food safety related risks.

- Published in Fresh produce

UAE ban on import of fruits and vegetables: the national standards is a priority

Thursday, 08 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

Translated version (brief) of my column in the arabic Al-Akhbar newspaper الحظر الإماراتي لاستيراد الفواكه والخضار: سلامة المعايير الوطنية أولويةhttp://www.al-akhbar.com/node/276723 Recently, the UAE banned the importation of vegetables and fruits from Lebanon and other countries because they contain high levels of pesticide residues that exceed the permitted levels according to their own standards. According to Al Bayan newspaper published in Dubai on 25 April 2017, the ban includes all types of apples from Lebanon. There is no doubt that this decision affects primarily farmers, and thus the process of accessing markets and avoiding the surplus, which has become a chronic problem for this sector. What are the backgrounds and present conditions of Lebanese fresh produce and how can it be improved? In general, the States establish their national standards to determine permitted levels of pesticide residues, and when countries lack the resources to establish their own national pesticide management program, they adopt the international standards developed by the WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission. According to regulations, It is permitted to use pesticides that have been scientifically proven to be effective without causing harmful effects to consumers, farmers, animals, and the environment. The use of pesticides is authorized or approved after the maximum residual limits (MRLs) in food or feed products are determined. It should be noted that exceeding the permissible limits does not necessarily mean the levels of residues pose a risk to human health because the permissible limits are so determined that the resulting exposure to MRL is much lower than the levels that can cause a serious or chronic health hazard. However, this does not eliminate cases where the residues beyond acceptable limits may pose a health risk to the consumers and require rapid intervention to withdraw products from the markets. Another important reason is that GAP standards and permissible limits for pesticides may differ from one country to another, i.e., the MRLs of the importing countries are higher than what is actually being applied in the exporting country. Agricultural Extension The UAE’s rejection of Lebanese products is nothing new. In 2001, the United States rejected 27% of food exports from Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria due to non-compliance with food safety measures (filth and microbiological contamination, high levels of pesticide residues). Between 2010 and 2013, a project funded by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) was implemented with the aim of promoting the production and marketing of Lebanese agricultural products and ensuring food security, quality system, and good practices. The project focused on the development and application of good agricultural practices targeting three major crops: grapes, citrus, and apples. This has called for the establishment of a technical working group (TWG) to facilitate the adoption of international or national standards, quality assurance systems, food safety and environmental management by fruit and vegetable producers and other actors in the agricultural production chain. However, until 2016, the proposal to establish the TWG was not yet been ratified. In fact, the good agricultural practices and the integrated pest management are promoted through extension services. However, since 2005, Lebanon has not had an updated budget to cover these areas. The agricultural sector has relied on external financing that does not provide a sustainable solution and may lead to several risks associated with improper agricultural practices, especially in the absence of national laws and standards. Bacterial contamination in the food chain In this context, I would like to shed light on our study that was published in the Journal of Food Control (2016) and that was partially funded by the National Council for Scientific Research which examined the microbiological safety of fresh produce (vegetables) from farm to the wholesale market. The results showed high levels of fecal indicators (E. coli and coliform) on parsley, lettuce, and radish and that the contamination levels increased from the fields to the washing facilities indicating possible sources of contamination at all stages of the food chain and particularly in the post-harvest washing stages where Salmonella was isolated. The presence of other pathogenic microorganisms, Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus in 14% and 45% of the samples taken from the fields and all the points of the chain to the restaurants (restaurants were covered in a separate work) respectively, were concerning. The fieldwork has shown unacceptable hygiene standards throughout the post-harvest stages and the use of untreated wastewater for the irrigation of crops. Details are available in here. Along these lines, parsley and lettuce in the wholesale market were classified by size. It was common, for example, to hear that parsley or lettuce that are irrigated with sewage are bigger and therefore more profitable. I will put here some quotes from the interviewed farmers : “I know this water is contaminated with nitrates and other chemicals, but the use of sewage does not hurt.” Or someone else who said: “lettuce is bigger with the use of sewage”, and ” the sewage gives a bigger size and reduces the use of fertilizers”. Another said, “ the polluted water of the river does not hurt, see how this lettuce looks great!” It is well recognized that bacteria can be transferred to agricultural products through irrigation and post-harvest wash water; hence, in the Leafy Green annex of the Code of hygienic practice for fresh fruit and vegetables-CAC/RCP 53–2003, Codex Alimentarius provided general recommendations stating that water that comes into substantial contact with the edible portion of the leafy vegetable should meet the standards for potable or clean water, i.e., which meets the quality standards of drinking water such as described in the WHO Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality and or that does not compromise food safety in the circumstances of its use. The entry to the international markets is a major challenge considering the growing burden of food outbreaks associated with the consumption of fresh vegetables and fruit and so the strict monitoring and constant updating of international standards such as the FDA Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) which introduced a comprehensive reform of the food safety laws and imposed stringent

- Published in Food safety and trade

من يعالج الأمراض الناجمة عن تلوث الليطاني والمزروعات؟

Thursday, 08 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

موضوع تلوث مياه نهر الليطاني ليس بالجديد. لطالما تردّد أن الأسباب الرئيسية لتلوّث مياه نهر الليطاني هي غياب النظم الفعّالة لمعالجة مياه الصرف الصحي والنفايات الصناعية السائلة غير المعالجة التي تصبّ كلّها في التربة والمياه وقطع طريق النهر بسد القرعون. وقد تكثّفت الاجتماعات التي كان آخرها أمس للمعالجة، ولكن ما هي المخاطر التي تشكلها تلك الملوثات على الصحة والتي كانت معلومة منذ بداية التسعينيات؟ وما الذي حال دون معالجة الوضع البالغ الخطورة؟ هذه الكارثة البيئية إنما هي بالأحرى شبكة معقدة من مشاكل مزمنة تهدّد الصحة العامة، وتدعو إلى تدخل حكومي طارئ لضمان التشريعات السليمة في ما يتعلق بمخاطر الصحة العامة موضوعي في جريدة الأخبار

- Published in Fresh produce

COVID-19 Preparedness in the Food Industry

Thursday, 08 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

On 11 March 2020, the outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization as the virus has spread to many countries. It’s the first time the WHO has called an outbreak a pandemic since the H1N1 “swine flu” in 2009. What is confirmed is that the virus is transmitted through direct contact with respiratory droplets of an infected person (generated through coughing and sneezing). Individuals can also be infected from and touching surfaces contaminated with the virus and touching their face (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth). Besides, the COVID-19 virus may survive on surfaces for several hours, yet disinfectants can kill it. On 9 March, the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) stated on their website that there is currently no evidence that food is a likely source or route of transmission of the novel coronavirus, and that they are closely monitoring the situation as any new information about the outbreak comes to light. EFSA’s opinion is based on the fact that previous outbreaks of related coronaviruses, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), show that transmission through food consumption did not occur. BfR, the federal institute of risk assessment in Germany concurred with the findings, stating that there are currently no cases that have shown any evidence of humans being infected with the new type of coronavirus by another method, such as via the consumption of contaminated food or via imported toys. Transmission via surfaces which have recently been contaminated with viruses is, nonetheless, possible through smear infections. This is only likely to occur during a short period after contamination, due to the relatively low stability of coronaviruses in the environment. This virus is not SARS, it’s not MERS, and it’s not influenza. It is a unique virus with unique characteristics WHO Director General A recent review analyzed 22 studies and revealed that human coronaviruses such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) coronavirus, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) coronavirus or endemic human coronaviruses (HCoV) can persist on inanimate surfaces like metal, glass or plastic for up to 9 days, but can be efficiently inactivated by surface disinfection procedures with 62–71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide or 0.1% sodium hypochlorite within 1 minute. Other biocidal agents such as 0.05–0.2% benzalkonium chloride or 0.02% chlorhexidine digluconate are less effective This is what we know “so far”. As the WHO Director-General stated “This virus is not SARS, it’s not MERS, and it’s not influenza. It is a unique virus with unique characteristics”, and scientists are working around the clock to address critical gaps in knowledge. In a recent study (US government work) conducted by the National Institutes of Health, Princeton University and the University of California, Los Angeles, with funding from the U.S. government and the National Science Foundation, Covid-19 was detected up to three hours later in the air, up to four hours on copper, up to 24 hours on cardboard and up to two to three days on plastic and stainless steel. Revise and update the health policy Having said that, while there is a lot of uncertainty in the situation, it is advisable that food processors evaluate the current practices inside their organization and manage staff who may be carriers or infected with the Coronavirus. Reviewing and updating the existing disease control/health policy while considering recent recommendations and requirements of the local authorities is paramount. Did you address in your your policies address any food to which an ill employee may have had exposure, including whether the policies address whether there are conditions present that would support a company decision to place food on hold pending advice from the public health authorities. Here are the CDC recommended strategies for employers to use which may help may help prevent workplace exposures to acute respiratory illnesses, including COVID-19. Many of the steps described in the CDC link are useful and apply to every food facility, yet as a food facility outside the US, you will refer to the guidance, updates and travelers’ health notices of local authorities to determine whether there are any local requirements to contact public health authorities in the event an employee in the workplace has been diagnosed with COVID-19 and to establish procedures for handling other employees who may have come in contact with the diagnosed employee. Top management should encourage employees with symptoms to stay home and get prepared for the sudden absenteeism and shortage of staff. Besides the disease control plan, precautionary hygiene measures are of significant importance. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has issued recommendations including advice on following good hygiene practices during food handling and preparation, such as washing hands, cooking meat thoroughly and avoiding potential cross-contamination between cooked and uncooked foods. Similarly, many local authorities such as in Belgium also emphasized those practices. As simple as this seems to be, translating messages into practices is not easy and often undermined with barriers that need to be understood. In practice, it requires instilling a hygiene culture to ensure the highest levels of hygiene measures, particularly when food processors may face the situation of operating with staff shortages and absenteeism. A hygiene culture in a way it does not require the staff to think much about it! it is a culture shared at all levels of the organization from top management to production staff. Have you included in your contingency plan re-evaluating your hygiene standards? The topic of today is focused on hand hygiene, which must not be overlooked in your Covid-19 training tool box. What have you done to highlight this issue in your organization? It would be great if you share your experience with others in the comment box. I am sharing some of the key messages you may like to consider to reinforce the hand washing practices: Hygiene Culture 1- Assign competent staff to stay aware of recent news and updates on the COVID-19 outbreak, how it is transmitted and how to prevent transmission. Information are available on the CDC, ECDC, WHO websites, and local health authorities.

Avoid the mistake of assuming HACCP and GFSI compliance will meet the FSMA requirements

Thursday, 08 October 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

I have met recently with few representatives from the food industry and it appeared from our discussions that many were still unaware of the difference between the GFSI certification and FSMA compliance. For them, both equate, and the only steps required to export foods to the US market is to go through the registration process. There was some confusion about the mandatory requirement to develop and implement a Food Safety Plan (FSP) which was assumed to be the same as their existing HACCP plan, which is not the case. Certification to a GFSI-benchmarked scheme (BRC, SQF, FSSC22000, IFS, etc.) and having an HACCP plan do not make the food facility compliant with the FSMA Preventive Controls Rule, yet it does make it ready to reach compliance. While HACCP focuses on the determination of the Critical Control Points (CCPs) to prevent post-process contamination, under FSMA, the FSP goes far beyond the determination of the CCPs during processing to include risk-based preventive controls that are determined as critical elements in the sanitation and allergen control programs, and in the supplier chain program. The FSP must be created and overseen by a preventive controls-qualified individual (PCQI) and should be based on: 1- Hazard Analysis, identifying known or reasonably foreseeable biological, chemical, radiological and physical hazards 2- Documentation (written) of preventive controls including process controls, food allergen controls and sanitation controls, supply chain controls, and a recall plan 3- Documented implementation procedures which include monitoring the implementation of the preventive controls, corrective action, and verification procedures. To export foods to the US market, It is mandatory to develop the Food Safety Plan that is compliant with FSMA Preventive Rule, NOT with HACCP The difference between HACCP and GFSI compliance or to FSMA might not be practically easy to grasp without a PCQI training. Why it is important to train PCQIs? Under the FSMA rule, FDA is permitted to inspect domestic and foreign facilities (those based on non-US territories) at the times and in the manner permitted by the FD&C Act. As part of this, the FSP is inspected for its adequacy and any deficiencies or inadequacies identified means the PCQI (individual who developed the FSP) is not appropriately trained for the application of the risk-based preventive controls. The difference between HACCP / GFSI compliance and FSMA might not be practically easy to grasp without a PCQI training What may result out of this? In the event of having an inadequate food safety plan developed by unqualified staff, various scenarios are possible depending on the severity of the identified failure or if the food presents a threat of serious adverse health consequences or death to humans. Therefore, the FDA can take actions such as: suspension of the food facilities’ registration, product detention, issuing a warning letter and criminal charges and add to this the costly re-inspection visits. The cost for a foreign facility is $285 per hour. Ensuring the FSP is prepared and overseen by a trained PCQI is certainly an added value and crucial to avoid the above mistakes. To help the food industry complies with the requirements of the Preventive Controls rules, the Food Safety Preventive Controls Alliance (FSPCA) developed the FDA-approved standardized curriculum for training PCQIs. As a PCQI Lead Instructor, I am offering public and in-house FSPCA certified PCQI training. For more information on locations and dates, please follow the link here and navigate the calendar. You are welcome to subscribe to the newsletter to keep you updated on the PCQI training that will be organized in Germany and selected countries in the MENA region for the year 2019.

- Published in FSMA

How Does HARPC system differ from HACCP

Sunday, 26 April 2020

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

“What is the difference between the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) and the Hazards Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls (HARPC)?” is a question we often hear from professionals working in the food industry and expected to be raised more often having been involved in managing the food safety systems based on the HACCP concept which is universally accepted by government agencies, trade associations and the food industry around the world ( NACMCF, 1997). HACCP is based on the analysis and control of biological, chemical, and physical hazards from raw material production, procurement and handling, to manufacturing, distribution and consumption of the finished product in order to reduce the risks of safety hazards in food. It is based on 7 principles: Principle 1: Conduct a hazard analysis.Principle 2: Determine the critical control points (CCPs).Principle 3: Establish critical limits.Principle 4: Establish monitoring procedures.Principle 5: Establish corrective actions.Principle 6: Establish verification procedures.Principle 7: Establish record-keeping and documentation procedures The HARPC is based on these same basic food safety principles; more specifically, it recognizes the importance of hazards analysis and setting critical limits to monitor the control points; it emphasizes the corrections/corrective actions, verification activities and the recall plan. The preventive approach is not recent, it dates back to the 60’s when the HACCP was pioneered by the Pillsbury corporation to ensure food safety for the first manned National Aeronautics and Space Administration space missions. NASA’s main concerns were to ensure safe food for astronauts. The WHO Europe recommended the system in 1983 and the Codex released the first HACCP Guidelines which was revised in 2001 and adopted by the FAO/WHO Codex Alimentarius Commission. The U.S.National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods (Committee) reconvened a Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) Working Group in 1995. The primary goal was to review the Committee’s November 1992 HACCP document, comparing it to current HACCP guidance prepared by the Codex Committee on Food Hygiene. The Committee again endorses HACCP as an effective and rational means of assuring food safety from harvest to consumption. NACMCF issues the third revision document in 1997. Basically, the HACCP was integrated into the official regulations in the European Union and the United States. For instance, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration adopted HACCP in low acid canned foods, then the FDA mandated HACCP for seafood products and in 2001 for juice processors. The Council Directive no. 91/493/EEC places the responsibility of product safety on the industry as it introduced the concept of ‘own checks’ and Critical Control Points during processing and the Commission Decision 94/356/EEC details the rules for the application of the HACCP system. The term HARPC goes back to 2011, when the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) was signed into law by President Barack Obama. FSMA directs FDA to establish standards for adoption of modern food safety prevention practices by those who grow, process, transport, and store food. In 2015, FDA has finalized seven major rules to implement FSMA; the Hazards Analysis Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human food is one of those 7 rules which is also referred to as The Preventive Controls for Human Food (PCHF). The Hazards Analysis Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human food (HARPC) requirements specify that a facility must prepare, or have prepared, and implement a written food safety plan (FSP) (21 CFR 117.126). The elements of the FSP are (21 CFR 117.126(b)): Hazard analysis Preventive controls (see 21 CFR 117.135), as appropriate to the facility and the food, to ensure safe food is produced, Procedures for monitoring the implementation of the preventive controls, as appropriate to the nature of the preventive control and its role in the facility’s food safety system Corrective action procedures, as appropriate to the nature of the hazard and the nature of the preventive control Verification procedures, as appropriate to the nature of the preventive control The preventive controls approach to controlling hazards used in an FSP is developed based on the risk-based HACCP principles as described by the National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods It is important to note that the preventive controls approach to controlling hazards used in an FSP is developed based on the risk-based HACCP principles as described by the National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods. Therefore, there are similarities between the FSP and a HACCP plan and the similarities are in the essence of both systems; both adopt the preventive approach , yet there are few differences. Table 1 shows the different elements required in each of the plan and how they differ: In HARPC, A “hazard” is any biological, chemical (including radiological), or physical agent that has the potential to cause illness or injury. These include hazards that occur naturally, that are unintentionally added or that may be intentionally added to a food for purposes of economic gain (i.e., economic adulteration). Contaminants that have no direct impact on the safety of the products are considered “undesirable defects” and do not require a preventive control, hence they should not be included in the FSP. Once the hazards requiring preventive controls are identified in the Hazard analysis, the FSP should include documentation of the preventive controls that were determined as appropriate to controlling the hazards. The preventive controls include: Process controls Food allergen controls Sanitation controls Supply-chain controls Recall plan Other controls The CCP is a point, step or procedure at which controls can be applied and a food safety hazard can be prevented, eliminated or reduced to acceptable (critical) levels. In a HACCP plan, the CCPs are steps in the process that are always monitored, whereas in the FSP, not all preventive controls are CCPs (Process controls), hence the preventive controls are only monitored as appropriate to the nature of the preventive control and its role in the facility’s food safety system. That means some preventive controls that are not necessary applied at CCPs may not be monitored such as the supply chain preventive control and recall plan. The FSP incorporated the element “corrections” in addition to

- Published in FSMA