Food labels review for entry to the US, EU and UK markets.

The All-Too-Human Causes of Food Safety System Shortfalls

Sunday, 29 August 2021

by Dr Faour Klingbeil

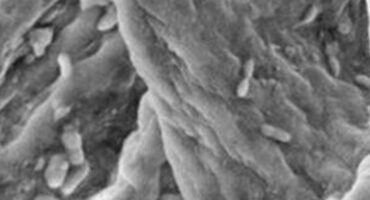

Moving from knowledge-based to behavior-based training might be key to culture change An article published in the Food Safety Magazine, August 12, 2021 Given the continued growth of trade agreements and exchanges between countries and the evolution of production methods to meet international market needs, our food supply has developed significantly over the last several decades. A wide array of our food products are made from ingredients and packaging sourced from different suppliers worldwide, resulting in rapid movements of food products and globalized food transport. The “international agro-food trade network,” constructed using the United Nations (UN)’s food-trade data, shows the dense web of food trade connections among seven central countries that trade with more than 77 percent of the 207 countries from which the UN gathers information.1 While this vast trade network enhances accessibility to food, considerable risks emerge with the amplified production and intensive handling of raw materials across the supply chain, further complicating the tracing of food sources or foodborne hazards in multiple actors’ global supply chain. Given the continued growth of trade agreements and exchanges between countries and the evolution of production methods to meet international market needs, our food supply has developed significantly over the last several decades. A wide array of our food products are made from ingredients and packaging sourced from different suppliers worldwide, resulting in rapid movements of food products and globalized food transport. The “international agro-food trade network,” constructed using the United Nations (UN)’s food-trade data, shows the dense web of food trade connections among seven central countries that trade with more than 77 percent of the 207 countries from which the UN gathers information.1 While this vast trade network enhances accessibility to food, considerable risks emerge with the amplified production and intensive handling of raw materials across the supply chain, further complicating the tracing of food sources or foodborne hazards in multiple actors’ global supply chain. Indeed, a loss of control or oversight at any step of the supply chain could lead to detrimental economic and public health consequences. In 2011, one of the largest outbreaks of a foodborne illness was caused by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O104:H4. The deadly strain caused approximately 3,000 hospitalized cases, 855 of them due to hemolytic uremic syndrome. It also led to 55 deaths, primarily in Germany, with scattered cases in 15 other countries in Europe and North America. As the strain source was still unknown, the blame was falsely directed at Spanish cucumbers and tomatoes. Consequently, a Russian ban on imports of all European Union fresh produce, followed by the EU’s ban on the import and sale of fenugreek seeds, which was eventually shown to be the culprit, caused substantial economic losses to farmers and industries.2 Such an outbreak demonstrates how local infection agents can bring about widespread economic and health threat. “Food safety systems are vital to control food safety risks, but they are not a silver bullet.” Dima Faour-Klingbeil Understanding Global Challenges Inadequate Food Safety Management Systems The global food market’s rising challenges rationalize the strict measures the food industry should take and the urgency to adopt stringent risk-based preventive food safety standards to minimize the health risks associated with consuming unsafe food products. Introduced in the 1960s by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) preventive approach was further developed by the food industry (i.e., Pillsbury). Later on, HACCP was advocated and promulgated by international organizations and mandated by regulatory agencies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as an effective preventive tool to manage the hazards throughout the farm-to-fork continuum and reduce the risks associated with foodborne diseases. At the same time, driven by legal obligations to exercise due diligence and safe food production, industry stakeholders, such as retailers and nonprofit organizations, developed voluntary private food safety standards that integrate the HACCP system advocated by Codex Alimentarius to protect the reputations of businesses. Although voluntary, they generally became de facto mandatory standards that set out requirements for a risk-based food safety management system that were stricter than regulatory standards. Progressively, they were established to ensure compliance with customers’ demands and regulatory requirements while addressing fraud and intentional adulteration in a global market. Food safety systems are vital to control food safety risks, but they are not a silver bullet. Despite improvements in prevention systems, food recalls and illness outbreaks continue to hit the headlines, sometimes caused by food companies that passed certification audits of their food safety systems. A case in point is the massive multistate Salmonella outbreak caused by Peanut Corporation of America, which reportedly scored high on a third-party certification audit report.3 Read all the article in the Food Safety Magazine

- Published in Food safety and trade